Gentrification and Resilience: Preserving Filipino Heritage in San Francisco’s SOMA Pilipinas Filipino Cultural Heritage District

As the corporate exodus from California continues, the Bay Area’s landscape is undergoing a swift transformation, leaving behind vacant spaces and raising concerns about the future for the SOMA Pilipinas Cultural District in San Francisco. Once a thriving economy where space was scarce, the district has felt the impact of numerous businesses shuttering. Media outlets like SF Gate and Santa Clara Business Law Chronicle attribute California’s high corporate income tax rate, steep state sales tax rate, tax laws and restrictive regulations as being the drivers behind the corporate and retail migration. This raises critical questions about what lies ahead for the creative and entrepreneurial communities of color in the SOMA and downtown.

The mass departure of primarily tech companies presents a double-edged sword for the Filipino-American community working, living, and creating in the city’s South of Market neighborhood (affectionately referred to as “SOMA” by locals, but also known as the Filipino Cultural District). As space increases and rental rates decrease, there is both the opportunity for revitalization and the risk of further self-gentrification. Community leaders like Kultivate Labs’ Executive Director, Desi Danganan, emphasize the need for cautious, inclusive growth in addressing these obstacles. Danganan’s recent reflections on Episode 34 of Balay Kreative’s Cultural Kultivators podcast underscore the fears surrounding development in SOMA, where efforts to enhance the community could inadvertently lead to increased real estate prices, once again displacing long-time residents who have cultivated the corridor’s unique cultural identity. He articulates, “If we make SOMA Pilipinas a viable, enriching, cool place to live, that the real estate values are going to go up and that Filipinos would inadvertently get pushed out” (Cultural Kultivators). The gentrification of Williamsburg in Brooklyn, New York and Wynwood in Miami illustrate this fragile balance between urban renewal and genuine cultural revitalization.

SOMA’s evolution is better understood as part of a broader pattern of gentrification that has historically targeted communities of color in San Francisco. To better comprehend our present and future, we must reflect on the history of gentrification in SOMA Pilipinas and its enduring impact on the Black and Brown communities who have long called the area home. San Francisco’ South of Market (SOMA) neighborhood has remained a cultural stronghold for the city’s Filipino community, even as relentless waves of gentrification have displaced many of its residents.

Thea Quiray Tagle, Photo Source: https://ybca.org/artist/thea-quiray-tagle/

As Filipinx femme curator, writer, and scholar, Thea Quiray Tagle, PhD notes:

“The forty-year-long San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA) campaign to rid the city of ‘urban blight’ and rebuild the city as an international banking capital” (Tagle).

These ‘redevelopment’ policies prioritized corporate interests and profit over the needs of the city’s working class residents and creatives, who have contributed to the city’s dynamism.

Kapwa Gardens, Photo Source: kapwagardens.org

The establishment of the SOMA Pilipinas Cultural District and city-owned public spaces like Kapwa Gardens represents an intentional effort to uplift and provide a safe space for Filipino families in San Francisco, who have been marginalized by these systemic changes. Yet, SOMA also stands as a symbol of Filipinos’ cultural resilience and dedication to kapwa in the face of ‘urban renewal.’

Before the formal recognition of the SOMA Pilipinas Cultural District, Filipino folks formed communities in Manilatown, a bustling enclave along Kearny and Jackson Street. In the 1920s and 30s, it served as not just as a community and commercial hub for the Filipino community, but also a sanctuary from the pervasive racism and xenophobia in American society.

Photo Source: https://www.ihotel-sf.org/

Manilatown was all but obliterated by ‘beautification projects’ that made space for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and Yerba Buena Gardens. The violent removal of residents from the International Hotel (I-Hotel), a key site in Manilatown, remains a painful testament to the destructive force of gentrification.

The I-Hotel, a refuge for the manong and manang generation and their descendants, was the final building in Manilatown to stand before its residents were forcibly evicted. As Tagle poignantly observes, “The International Hotel’s loss marked the destruction of the first Filipino-American ethnic enclave within city limits” (Tagle).” Despite its tragic demise, the movement to save the I-Hotel galvanized a broad coalition of marginalized Black and Brown communities outside the Filipino community, highlighting the enduring power of solidarity. A community is not just a place; it is its people—those who drive and document shared history, cultural expression, and collective action. The fight to save the I-Hotel was foundational to Third World alliances in the Bay Area, influencing communities and organizations today, as they unite to resist displacement and assert their rights.

Crowds jam Baker Beach in San Francisco to escape the 98 degree temperature. Eric Risberg/AP Photo Source: https://www.businessinsider.com/photos-san-francisco-before-tech-boom-2016-8#san-francisco-is-ever-changing-20

San Francisco’s Dot Com Boom in the 1990s accelerated the gentrification process, driving up real estate prices with the influx of luxury housing and office developments. SOMA was one of few economically accessible neighborhoods, but suddenly the district’s long-standing residents were being pushed out—small businesses, low-income families, immigrants, and creatives who called the area home for nearly a century. What was once one of the last economically accessible parts of the city became unaffordable, leaving working-class and immigrant families struggling for their livelihood. The repeated eviction of SOMA’s Filipino population is not just a battle over real estate; it’s a deeper struggle for cultural preservation, collective memory, and the right to remain rooted in a rapidly changing city.

Anti-Eviction Notice, Photo Source: SOMCAN via https://www.somapilipinas.org/policy-advocacy-racial-equity

Despite these challenges, the mission to preserve SOMA’s Filipino heritage and history persists. Organizations like South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), Anakbayan SF, SOMA Pilipinas, and Kultivate Labs continue to advocate for Filipino and Black and Brown residents’ rights.

2024 HIRAYA Bringing Filipino Vision to Light, Kultivate Labs Team

Photo Source: Marky Enriquez

Kultivate Labs is an organization that champions economic development, and platys a unique role in helping reconstruct the cultural corridor along Mission St.

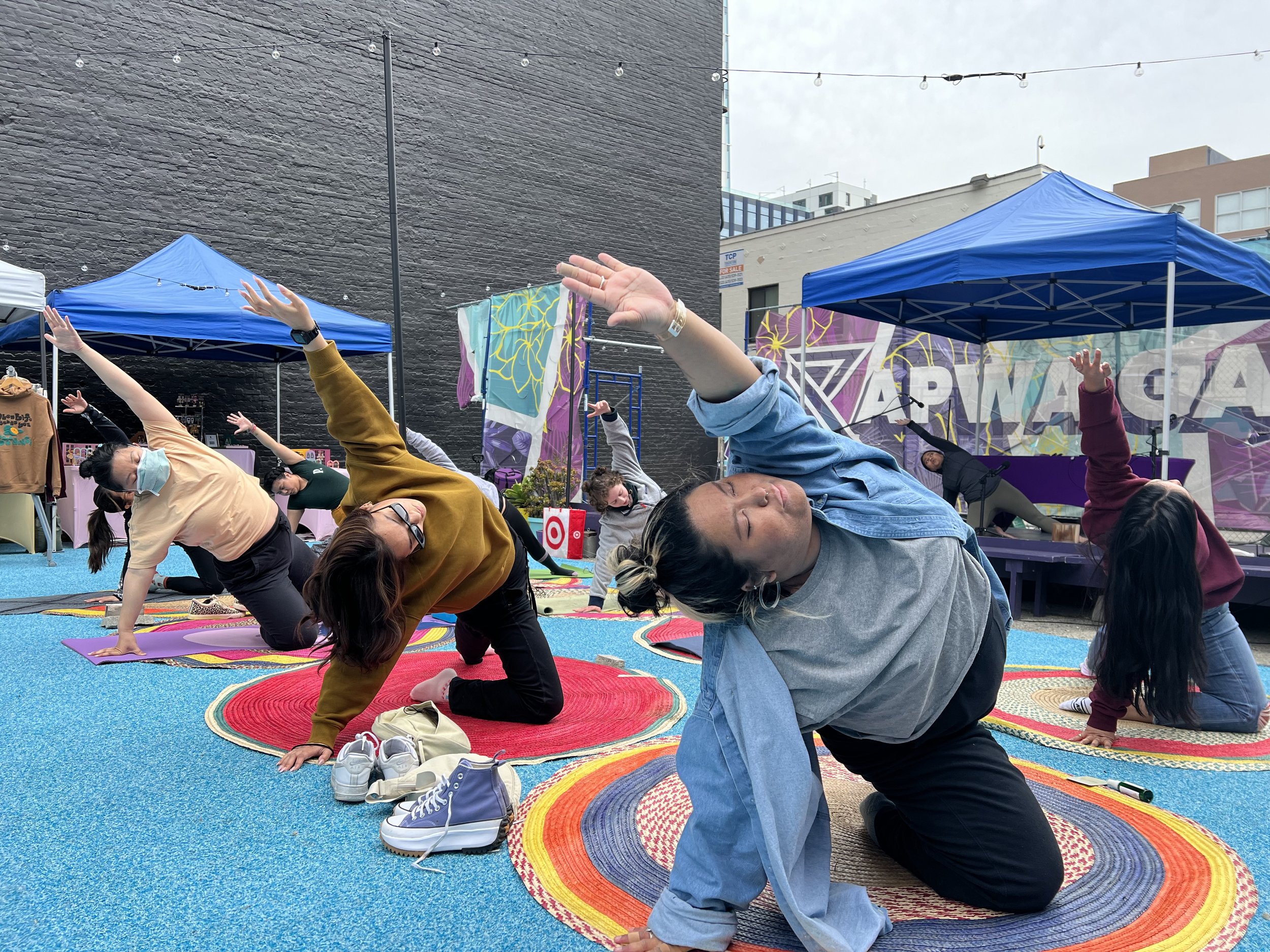

Through initiatives like UNDSCVRD SF – a multi-location block party and culture crawl – Kultivate Labs has constructed a platform for Filipino-owned business, artists, and creative to network and thrive. Thousands of attendees gather year after year to celebrate Filipino food, art, and music, offering economic opportunity and a counter-narrative to the forces of gentrification and corporate migration.

Together with the rest of these organizations – with SOMA Pilipinas as the leading voice and face of the district – we work to keep SOMA’s cultural roots, well, rooted amongst ongoing challenge like socioeconomic strife and crab mentality.

Photo Source: Ken Villa

In response to the swell of commercial vacancy rates, Kultivate Labs emerged under Desi Danganan’s leadership to assist with the revival and maintenance of the SOMA Pilipinas Cultural District, attract more Filipinos to the area, and create a commercial corridor for communities of color. Now in its eighth season, Kultivate has aided the establishment of eight Filipino businesses in SOMA across food and retail. Danganan dreams of bringing a “Filipino enclave” into existence, where Filipino entrepreneurs are “appreciated, [and given] money by the city to take over the streets” (Prism).

He recognizes the importance of pop-up businesses, or “pop-ups,” as incubators for growth and sees them as potential permanent fixtures in SOMA, further strengthening the district’s cultural fabric. Desi Danganan emphasizes the need to shift landlords’ perception of these “pop-ups,” which the latter often views as temporary. For Danganan, these ventures represent long-term potential and opportunities for small businesses to become the next Izzy and Wooks, Dabao Singapore, or like any of Kultivate Labs’ success stories through SEED Network.

Photo Source: Work Play Branding

Gina Mariko Rosales, CEO of Make it Mariko, co-creator of UNDSCVRD shares a vision for repurposing vacant spaces in SOMA, such as the San Francisco Centre and the Metreon, with Filipino- and Black- and Brown- owned pop-ups–inspired by Montreal’s festival infrastructure. Rosales and Danganan envision SOMA Pilipinas Cultural District as an abundant hub of creativity and commerce that collaborates with communities external who face similar socioeconomic displacement, to create and share frameworks for retaining cultural impact in the neighborhoods they’ve built. Although Kultivate Labs and SOMA’s own residents grapple with the reality of media coverage painting the underserved neighborhood as a dangerous dystopia, they’re also the living testimonial that the district – with all its concrete roses and thorns – is home to a vibrant culture deserving of a far more nuanced narrative.

Photo Source: Marky Enriquez

Desi also shares insight on the “crab mentality” prevalent in the Bay Area Filipino-American community, which resonates deeply with the tension between local organizations finding a balance between aspiration and preservation. He advocates for envisioning beyond mere curation, and toward creating equitable opportunities that are uplifting and accessible for small businesses and creatives.

Through events like the Hiraya fundraising soirée and UNDSCVRD SF, as well as programs like Brownthought Academy and Kreative Growth, Kultivate labs seeks to redefine economic growth and generational wealth in a way that honors its heritage, while fostering a sustainable path forward.

The Filipino community’s fight to make our ancestors’ dreams reality, and Black and Brown struggle for a common cause, remains vital as the Bay Area’s economic inequities shift and persist. The ‘common cause’ is nothing less than the preservation of home and history—both its physical spaces and its cultural soul. SOMA’s past and present are markers of our community’s strength and resilience in the face of gentrification and displacement.

The future of the district depends on the continued unity and kapwa of its residents, who understand that cultural preservation is resistance. As the Golden State Warriors’ slogan suggests, there is “strength in numbers.” This strength will be key in ensuring that the abundant history and cultural identity of SOMA Pilipinas Cultural Districts remain intact for future generations.

The history of displacement in San Francisco’s Filipino American community goes beyond the district and city itself. As families were uprooted from San Francisco, many relocated to surrounding areas, including the military towns of Vallejo and Richmond in the North Bay, Antioch, Tracy, Dublin; as well as the suburbs of Daly City and Fremont. Suburban migration – both forced and voluntary – is another chapter of our community’s erasure and removal, as Filipino-American families continue to seek affordable housing and economic or creative opportunities beyond the increasingly inaccessible boundaries of the city.

For your convenience + curiosity, we’ve included links to community orgs doing important work in the SOMA Pilipinas Cultural Heritage District, and all across the Bay Area. Feel free to explore!:

Cited Sources:

Baladjanian, Chandler, and Robin Rhim. “The Corporate Departure from California.” SCBC, Santa Clara Business Law Chronicle, 23 Apr. 2024, www.scbc-law.org/post/the-corporate-departure-from-california#:~:text=California’s%20tax%20laws%20and%20prohibitive,have%20decided%20to%20leave%20California.

Carlsson, Chris, “Shaping the City from Below: San Francisco’s history offers lessons for the future.” Boom, University of California Press, 1 June 2014; 4 (2): 94–102. https://online.ucpress.edu/boom/article/4/2/94/106581/Shaping-the-City-from-BelowSan-Francisco-s-history.

Kane, Astrid. “San Francisco’s Filipino Cultural District Eyes the Dying Westfield Mall.” The San Francisco Standard, The San Francisco Standard, 6 Aug. 2023, sfstandard.com/2023/08/06/soma-pilipinas-undiscovered-returns-san-francisco-westfield-mall/.

Martinez, Alexandra. “San Francisco Nonprofit Looks to Revive Local Filipino Culture.” Prism, 2024 Prism, 16 Aug. 2023, prismreports.org/2023/08/16/san-francisco-nonprofit-filipino-culture/.

Tagle, Thea Quiray. “After the I-Hotel: Material, Cultural, and Affective Geographies of Filipino San Francisco.” UC San Diego, California Digital Library, 2015, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/25b581sd.